How many oligo and polypeptides will you find in novelty skincare products? Start counting.

Proteins are like long words made of just 20 letters that can be repeated many times in different orders. Just like words, some amino acid sequences can form meaningful words or, in the case of proteins, working molecules. The amino acids are the letters, and the polypeptides or proteins are the words. If you give a monkey a typewriter (or, nowadays, a computer), it is unlikely that the monkey will produce a meaningful story or a lovely poem.

Oligopeptide: a few amino acids joined by peptide bonds

Polypeptide: many amino acids joined by peptide bonds

Proteins: large molecules comprising one or more long chains of amino acids

The proteins in our bodies are so meaningful, so carefully evolved, that each one does a great job at whatever it is that it does. Even short peptides, like glutathione, are great at what they do, with glutathione carrying reducing (anti-oxidizing) power around. It does such an excellent job that the glutathione we use is the same that a bacterium like Escherichia coli uses. Changes would make it less effective or, more likely, useless. The same goes for long, complex proteins. A single change in a single amino acid can make a protein useless. If the protein is important, the embryo that carries such a mutation will not be viable. Such is the importance of amino acid sequences. You may have heard of metabolic illnesses caused by a single mutation in a single enzyme; they can cause havoc in the person that carries it.

How many polypeptides can you get by playing with the amino acid “alphabet”?

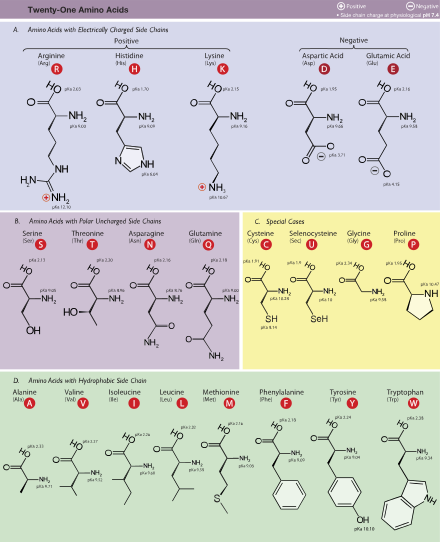

Nature makes many proteins. There are 21 amino acids (20 if you don’t count selenocysteine, and pyrrolysine is only used by some bacteria) used by our bodies to make proteins (proteinogenic). In real life you may find more than 20,000 proteins in the body, which will depend on the stage of development (how old we are), genetics, etc. But, in theory, how many peptides could you get by combining the amino acids humans use to make proteins? An infinite number.

The skincare industry is working hard at making up peptides, taking advantage of modern scientific methodology (initially developed for useful purposes!). Why? These days, peptides can be made by machines, and long proteins can be made by bacteria. Advertising uses novel peptides, because advertising has made them popular.

My main complaint about the INCI nomenclature is that it makes no difference between a real-life peptide (or a real-life protein) and peptides created by the imagination of (not a scientist) but an advertising guy. Why is that so bad? Because we know very well what glutathione (a real-life peptide) and epidermal growth factor (a real-life protein) can do for your skin and body. But nobody can tell you what a peptide created for advertising can do to you. While the best we can hope for is “nothing,” a major experiment is being done now on women who are paying exorbitant prices to be used as Guinea pigs, testing peptides that don’t exist in Nature.

Figure. Amino acids used in proteins. This is the alphabet used by Nature to make life.

How is a real-life protein made? How does it work? How did it evolve?

Throughout millions of years, proteins that worked for bacteria or algae were kept, duplicated, and, in some cases, changed to acquire a new function.Natural proteins, like epidermal growth factor, or papain, or defensin, have been tested by Nature for millions of years.

Synthetic peptides that are not identical to real-life peptides are a terrible idea unless they have been tested exhaustively. Why? Because the most likely result is that it will do nothing. It’s the equivalent of Shakespeare (Nature) and the monkey (the publicist). What’s the likelihood of a monkey typing on a computer writing a poem that makes sense? The same probability that a person trying to imitate nature when writing an amino acid sequence to be sent to a peptide synthesizer. You will get a peptide, yes. What will that peptide do once you apply it to the skin? What’s the probability that it will something useful? Very near zero.

Synthetic peptides can be very useful

Protein scientists work very hard, for decades, to crystallize proteins, determine their spacial architecture, find their active site and/or regulatory site, mechanism of action, etc. How do I know? Because I did it, and I have colleagues that still do it. This hard work is done for the protein that matters in our body, be it an enzyme (like SOD), a receptor (to bind to epidermal growth factor), a hormone (like estrogen), has a structural role(collagen), or whatever the protein does. This is done as a priority for defective (mutant) proteins known to cause illness.

An example of useful synthetic peptides is the medicines used to decrease appetite, like Ozempic. Here, the original peptide that exists in our bodies has been modified to extend the life of the peptide in the body so you can inject it once a week instead of every day. You don’t have to imagine how many experiments have been done to prove that Ozempic (or its relatives) are effective and safe. The FDA requires that the studies be made public and you can read those documents.

How many experiments have been done to prove that a novel peptide used in skincare is safe and effective? None. But if you want to be a Guinea pig and pay thousands of dollars for the privilege, that’s OK, as long as you are aware that you are a “mark.”

In the list below I discuss some ingredients used in the skincare industry. The word “inspired” means that an individual or company decided to use a natural protein as a model to build a short peptide to commercialize a skincare product. Some of these peptides may have some peer-reviewed research to show positive results, most don’t. Just think “monkey”, not Shakespeare.

Some examples of natural proteins and non-natural synthetic peptides used in the industry

Natural:

Carnosine: beta-alanyl-L-histidine, decreases rate of glycation of proteins, maintaining protein structure and function intact. Find carnosine in this Skin Actives product.

Glutathione: antioxidant peptide (see above) found in this Skin Actives product.

sh-Oligopeptide-1. Synthetic version of human epidermal growth factor, found in this Skin Actives product.

sH-oligopeptide-2. A synthetic version of human thioredoxin, an antioxidant protein. is found in this Skin Actives product.

sh- Polypeptide-3. Synthetic version of human keratinocyte growth factor, found in this Skin Actives product.

Superoxide dismutase. An antioxidant enzyme exists in many forms depending on the organism and cellular location. Find superoxide dismutase in this Skin Actives product.

Synthetic, non-natural:

Oligopeptide-177: inspired by erythropoietin, secreted mainly by the kidneys in response to oxygen depletion. Stimulates red blood production in bone marrow.

Palmitoyl tripeptide-8: synthetic peptide ester inspired by the α-melanocyte stimulating hormone (α-MSH), composed by the sequence N-(1-oxo hexadecyl)-L-histidyl-D-phenylalanyl-L-argininamide.

Syn-ake: tri-peptide inspired by waglerin-1 (22 amino acid peptide in snake venom).

Don’t expect these or other silly peptides to appear in Skin Actives Scientific products. We don’t try to innovate on Nature. We don’t have a G-d complex!

Hannah

References

Pál, C., Papp, B. & Lercher, M. An integrated view of protein evolution. Nat Rev Genet 7, 337–348 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1038/nrg1838

Ponomarenko EA, Poverennaya EV, Ilgisonis EV, Pyatnitskiy MA, Kopylov AT, Zgoda VG, Lisitsa AV, Archakov AI. The size of the human proteome: The width and depth. Int J Anal Chem. 2016;2016:7436849. doi: 10.1155/2016/7436849. Epub 2016 May 19. PMID: 27298622; PMCID: PMC4889822.

Claims on this page have not been evaluated by the FDA and are not intended to diagnose, cure, treat or prevent any disease.